We overestimate, sometimes.

We assume more people agree with what we agree upon. But, often, that is not the reality. We might be in ” false consensus”.

We overestimate.

The subject experts call it the ” false consensus effect”

It is a strong cognitive bias.

This effect came to light with Ross et al’s research conducted with Stanford University students in 1976.

Ross et al. study series: 1976

Ross and his team asked a group of students whether they agreed to walk 30 minutes around the campus wearing a signboard displaying “eat at Joe’s”.

They also asked another question from them:

Do you think your peers would agree to do that?

The results were as follows;

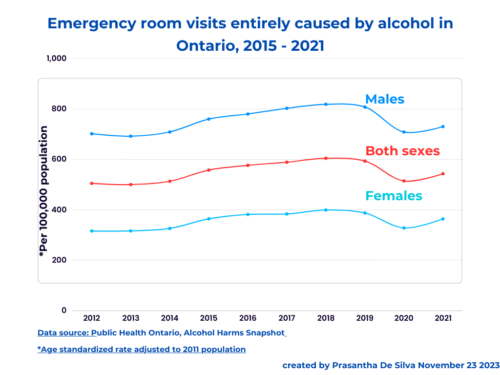

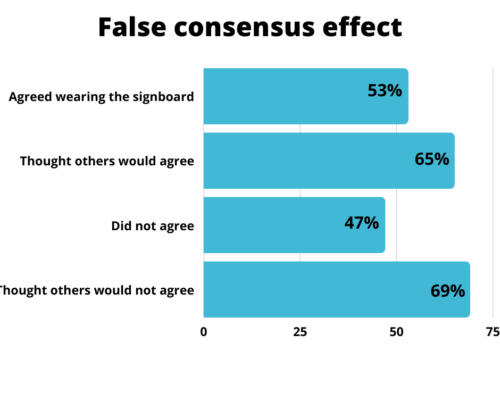

This is what the following graph says;

- Of those who agreed to wear the signboard, the majority (65 per cent) thought their peers would also agree to wear the signboard.

- Interestingly, of those who did not agree to wear the signboard, the majority (69 per cent) thought their peers would also not agree to wear it.

This is the “false consensus effect”. We think the majority would also think the same way that we think.

A meta-analysis on false consensus bias: 1985

A decade after the 1985 study of Lee Ross et al., Brian Mullen and his team meta-analyzed as many as 115 studies that tested this bias. These studies covered different topics: smoking, food choices, sports, politics, etc. The combined effects of all the studies became “highly significant and its effect sizes were of moderate magnitude”.

The false consensus among heavy drinkers:1986

In 1986, Wesley Perkins and Alan Berkowitz analyzed data that reflected attitudes about drinking from a representative sample of 1,116 college students in New York State. The data also included responses to survey questions about drinking behaviour. The students had to choose one out of five statements that best represented their attitude and their perception of their peers’ attitudes.

Of those five, two statements were as follows:

- “A frequent “drunk” is okay if that’s what the individual wants to do”.

- “An occasional “drunk” is okay even if it interferes occasionally with grades and responsibilities.

The above statements reflect very permissive (liberal) attitudes.

What do you think about their response?

Only 9.5% and 9.3% chose these two statements as their attitudes – altogether 18.8%; however, 29.5% and 33.2% perceived these statements as their peers’ attitudes respectively – altogether 62.7% of the total students responded!

They grossly overestimated – those who were in the minority perceived themselves as falsely in consensus with the majority – that the majority of their peers were with them.

This is how it happens; reasoning justifies themselves to continue their unhealthy drinking pattern. In this study, the researchers found that not only the group with liberal attitudes towards drinking demonstrated false consensus, but they also reported more drinking levels than those with restrictive attitudes.

This was not the only study; a series of studies at different universities demonstrated the prevalence of this bias.

The False consensus among Adolescent Smokers: 2009

In 2009, Otten et al. demonstrated this bias among Dutch adolescents. In addition to their smoking behaviour, these adolescents estimated the proportions of their

- 1= none of my friends smoke

- 2= less than 50% of my friends smoke

- 3=50% of my friends smoke

- 4= more than 50% of my friends smoke

- 5= all of my friends smoke

They found that regular smokers overestimated the prevalence of smoking of their friends significantly higher than friends of nonsmokers’ smoking.

Self-fulfilling Prophecy

What may happen next? The false consensus bias may lead to the “self-fulfilling prophecy” with time; the minority becomes the real majority due to the influence of the false consensus bias.

Contagiousness

Even those who do not hold the same attitudes may spread it like carriers spreading an infectious disease.