Updated on September 18, 2022

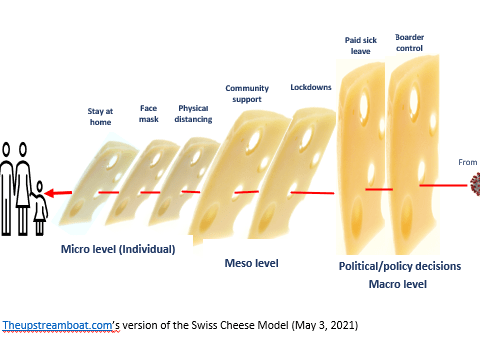

September 17 is the #patientsafetyday. This year’s theme is medication safety. WHO calls for urgent action for achieving medication without harm. Healthcare institutions employ the Swiss Cheese Model to prevent medication errors.

This post discusses this model and its improved version: The hot cheese model.

The Swiss Cheese Model and the Hot Cheese Model revolutionize the way we traditionally think of human error. In short, both models force us to move away from “blaming someone” for human error; instead, it pushes us to look at human error as a consequence, not as a cause. The Hot Cheese Model is an improvement to the classic Swiss Cheese Model.

About Swiss cheese

Following is a special type of Swiss cheese slice. It has holes in it. Among many, this is only one variety of Swiss cheese. This variety is from the Emmental area of Switzerland and is also known as Alpine cheese. It is yellow, medium-hard, and therefore not flexible.

A slice of Emmental Swiss cheese

Source: Emmental Swiss Cheese Slice; National Cancer Institute; Renee Comet (photographer): Wikimedia Commons on the public domain

About the Swiss Cheese Model

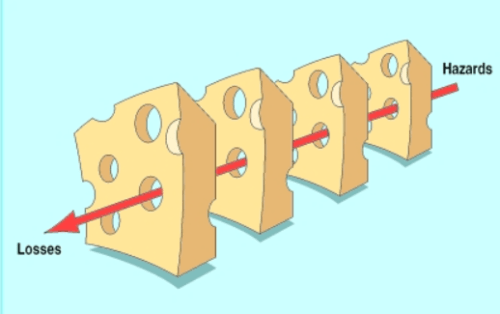

In 2000, James Reason, a professor in Psychology at the University of Manchester introduced this model. He published it in the British Medical Journal titled, “Human Error: models and management”. This is a “mental model” that helps us to visualize human errors in healthcare through a “system lens” instead of a “moral lens”. As a result, it forces us to move away from the emotional trap of the “blame game”.

James Reason’s Swiss Cheese model: Source: BMJ 2000 March 18.

This is one of my favourite conceptual models that helps to discuss behaviour change options without prejudice. I have used it before as a community physician at a private hospital’s family and corporate health program in Sri Lanka in 2014 after I retired from the government service.

Swiss Cheese Model in Patient Safety Newsletter

Following are James Reason’s thoughts about it;

Do not see human error as a moral problem

Think of deaths due to COVID-19. We, particularly those who hold authority, can easily find faults with the “general public” for not adhering to the recommendations; on the other hand, others can find faults with health officials, decision-makers, and politicians. We always fall into this trap of making it personal because blaming someone is emotionally satisfying.

Blaming individuals is emotionally more satisfying than targeting institutions.

James reason; “human error: models and management”, 2000, British medical journal

Instead, look at human error as a consequence, not as a cause.

James Reason conceptualizes that “humans are fallible and errors are to be expected even in the best organization system”. As a result, we need to see human errors as consequences, not as causes. In this paradigm shift, we do not have any room for the blame – game. In other words, this is an “upstream” journey; those who hold power cannot pass the ball down. Everyone has to bear equal responsibility and accountability.

This is the basic premise of this system approach. The systems approach forces us to think of humans as only a cog of a larger wheel of systems. So, here a human error is not seen as a failure but a variability. The focus is on the conditions or environments under which they operate or behave.

The Swiss cheese model’s systems approach

James visualizes this system approach in layers: Some are engineered such as alarms, physical barriers, automatic shutdowns, etc; others are human barriers such as physicians, pilots, and control room operators in the aviation industry. Procedures and admin controls are other layers.

Ideally, any layer should not have holes; but, in reality, there are many. And, the holes are dynamic; it constantly changes in size, shape, and shift location. Having holes in one or a few layers does not necessarily result in bad outcomes or disasters. Instead, holes in each layer need to be aligned together for a disaster to happen. When a disaster occurs, according to the model, one cannot look at only one layer; we need to examine all the layers to prevent it from happening again.

Active failures and Latent failures

He grouped the holes into two:

- Active failures

- Latent

The active “holes” consist of slips, lapses, fumbles, mistakes, and procedural violations. For example, administering the wrong drug is an active failure.

Sara Garfield and Bryony Dean Franklin in the Pharmaceutical Journal in 2016 describe those active holes drawing example situations from the pharmacy field;

| Slip | Intended to dispense one drug but dispense another similar to the prescribed one |

| Lapse | intended to dispense the second drug but forgot. |

| Violation | dispensed a controlled drug that did not meet the handwriting requirement |

| Mistake | dispensed the wrong form of the prescribed drug due to a lack of knowledge |

The Latent ones are the “holes” in the management decisions that lead to understaffing, time pressure, lack of facilities, unworkable procedures, etc. As its name suggests the latent conditions lie dormant for years in the system. He used another analogy here; active holes are like mosquitoes; although we can remove them one by one they keep coming. The Latent ones refer to the breeding places we can remove.

However, this model contains several limitations.

Hot Cheese Model: An improved Swiss Cheese Model

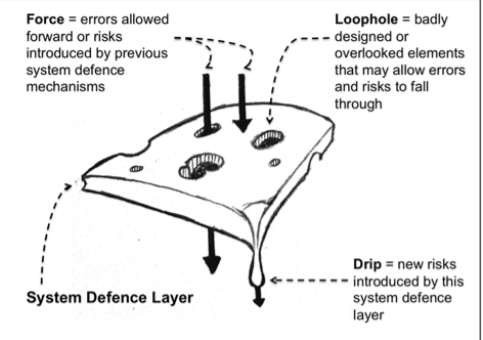

Li Y and Thimbleby H. 2014 introduced several improvements to the James’ Swiss Cheese Model and named it the Hot Cheese Model. This model addresses the limitations of the classic model. As the name implies, this Hot Cheese Model is hot, fragile, and flexible, and new holes can form with time. in contrast to the classic model, this model emphasizes that adding more layers does not necessarily bring more protection. It might add new holes to the system.

Hot Cheese Model; source: Li Y and Thimbleby H. 2014. Journal of Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh

A comparison between the classic Swiss Cheese Model and the Hot Cheese Model

Following are the key differences between the classic Swiss Cheese Model and the Hot Cheese Model.

- The original model sees managerial, policy, and procedural actions as latent ones. The Hot Cheese Model argues these layers are also active, not latent.

- The original model implies more layers to minimize the chances of error. The Hot Cheese Model argues more layers can also introduce more errors (drips) in addition to the errors that pass through from previous layers.

- The original model does not accommodate the shape-changing nature of a loophole. The Hot Cheese Model recognizes the hole’s shape can change with time. For example, those involved may find method short-cuts with time.

How the Swiss Cheese model can be applied in upstream public health interventions

The Swiss Cheese Model is often used to visualize how multiple barriers can contribute to the failure of a system, with each barrier represented as a slice of cheese. In the context of upstream public health interventions, the Swiss Cheese Model can be applied to understand how different factors can impact the effectiveness of public health programs.

Here are some examples of how the Swiss Cheese Model can be applied to upstream public health interventions:

- Access to care: The first slice of cheese might represent the barrier to access to care, such as a lack of transportation or long wait times. This barrier can prevent individuals from receiving the care they need to maintain their health.

- Provider bias: The second slice of cheese might represent provider bias or stigma, where healthcare providers hold biases or prejudices against certain populations that can impact the quality of care they receive.

- Lack of community engagement: The third slice of cheese might represent the lack of community engagement or trust in the healthcare system, which can prevent individuals from seeking care or following through with recommended interventions.

- Funding and resource constraints: The fourth slice of cheese might represent funding and resource constraints that limit the ability of public health programs to provide necessary services and interventions.

Each slice of cheese represents a potential barrier that can contribute to the failure of the public health system, and by addressing these barriers, public health programs can become more effective in promoting health and preventing disease.