We can use the Health Belief Model to craft health messages.

In this blog post, we will explore,

- The model’s origins,

- its evolution,

- how it works, and

- how it can be used to craft effective health messages.

Health Belief Model’s Origins

The model has a rich history.

It came to light in the 1950s with Godfrey Hochbaum’s research project.

This is how he conceptualised the model.

In the 1950s, pulmonary tuberculosis became rampant in some neighbourhoods in the US.

The US health authorities began screening at-risk people by X-raying their lungs to detect early changes.

The service was free. But, many did not attend.

To understand why they did not attend these free screening clinics, Godfrey Hochbaum surveyed 1200 randomly selected adults in three cities;

- 450 in Boston,

- 450 in Cleveland, and

- 300 in Detroit.

Their survey addressed the following two questions;

- What factors influenced community members in deciding whether to attend or not to attend the clinic?

- What factors influenced them to obtain the service after deciding to attend the service?

Each interview lasted more than an hour and covered themes related to participants’ beliefs, attitudes, and feelings regarding the activity including services’ administrative aspects.

In addition to traditional question items with closed and open-ended questions, they included projective questions that lead participants to awaken their subconscious level of thinking.

Perhaps, the most crucial finding was that

- Only 35% of those who knew that tuberculosis could exist without having symptoms obtained a chest X-ray.

This signifies that some other factors influenced their decision-making to attend the clinic apart from awareness. This holds even today – not all who know the usefulness of screening programs such as mammography and colonoscopy, do not attend those services.

The other findings were;

- 42% attended the service voluntarily without any symptoms.

- Another 16% attended due to their suspicion of having symptoms,

- Another 14% attended due to their significant others’ influence.

- Another 10% who attended did not show any consistent pattern.

- 17% did not participate in.

Godfrey Hochbaum published their results in a paper titled, ” Why people seek diagnostic X-rays?” in the Public Health Reports in 1956.

I am highlighting here two important beliefs/perceptions that he highlighted in this paper;

- Susceptibility

- Usefulness.

Perceived susceptibility

Of those who perceived that they were susceptible to getting the illness (perceived susceptibility),

- 82% attended the service. In contrast, of those who did not believe so, fewer than 50% attended the service.

Perceived benefits

Of those who believed that having an X-ray without symptoms would help to have better outcomes, 90% attended the service.

In this study, the researchers wanted to find out why some of those with a higher risk of contracting the disease did not attend the service. They found that the above findings held regardless of the study participant’s socio-economic status, age, and gender.

Methodological limitations

As pointed out by Rosenstock in his article on “Why people use health services”, the major methodological limitation was the study’s retrospective nature in that both existing beliefs and behaviour (having an X-ray) were inquired about at the same time. This is because people tend to change their previous perceptions in accordance with their later decisions as shown by Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory.

Kegeles’ study

In contrast to Godfrey Hochbaum’s retrospective study, Kegeles conducted a two-phase prospective study with individuals who had a pre-paid dental care plan and their subsequent preventive health visits: first, he inquired about their beliefs and second, three years later, about their visits to a dental clinic. Then he compared these findings with a control group from the same company. Both groups were stratified by age and marital status for analyses.

Following were his findings:

- 58.2% who felt susceptible made dental visits whereas 41.9% who did not feel susceptible, made dental visits. This finding was statistically significant, p* (X2 = 5.18) < .05.

- 47.5% who perceived the benefits of dental visits, made dental visits whereas 44.6% who did not perceive the benefits of dental visits made dental visits. However, this finding was not statistically significant.

- 67.3% who felt susceptible and perceived benefits if such visits made dental visits whereas only 38.1% of those who did not feel susceptible and perceived the benefits of such visits made dental visits.

The question they used to assess perceived susceptibility was, “How likely do you think that your worst dental problem or such a problem will happen to you again? The responses were likely and unlikely.

However, it is important to note here that they used open-ended questions during the first phase and close-ended questions during the second phase.

As summarized by Rosenstock, Kegeles found when both perceived susceptibility and perceived benefits exist together, more participants took action than those beliefs considered separately.

Rosenstock pointed out two important factors that needed to be addressed at that time: cues to action and perceived access to the services. However, He did not cite specific studies to support his claim. Instead, he referenced the following model presented by Becker (1974) tested in his study. I will discuss his methodology in a later post.

Health belief model: A decade later

A decade after the empirical testing of the Health Belief Model by Becker et al. in 1974, Janz and Becker published a review in 1984 in the Health Education Quarterly Journal.

They have reviewed 46 Health Belief Model (HBM) – related studies: 18 prospective and 28 retrospectives. It included both preventive health behaviours and sick role behaviours.

It included 3 studies of vaccination behaviour against Swine Flu, one vaccination study against influenza, one study related to screening for genetic disease (Tay-Sachs disease), four studies related to breast self-examination, and one study on high blood pressure screening.

Not only did studies on health promotion behaviours, but they also looked at medicine compliance behaviour studies. It included anti-high blood pressure compliance, adherence to dietary changes among individuals with diabetes and end-stage renal disease, the mother’s compliance with physician advice on the child’s health, and clinic attendance.

Overall, one important finding they mentioned (p.41) is that findings from the prospective study designs (which are superior designs to retrospective ones), were either similar or better than the findings from retrospective study designs.

This is great news.

According to their comparison of pre-1974 and post-1974 findings, “perceived susceptibility” topped as the most powerful variable in pre-1974 research whereas “perceived barriers” became the most powerful variable in post-1974 studies irrespective of the study design either prospective or retrospective and in the preventive and sick role behaviours. However, “perceived susceptibility” remains more important in preventive health behaviours than sick role behaviours. “Perceived severity” earned a much lower significant score (36% in the significant ratio) in preventive health behaviours whereas it rose up to 85% in sick role behaviours such as drug compliance.

The reviewers have correctly identified that the absence of standardised measuring tools for each HBM variable renders significant difficulties in the model appraisal process.

In 1974, Rosenstock found that perceived susceptibility to a problem and perceived benefits were the most powerful components of the model. However, he pointed out that the published studies at that time did not address cues to action and perceived accessibility (in other words perceived barriers). Then, Janz and Becker, a decade later found that perceived barriers as the most powerful variable.

Health belief model: 60 years later

In 2010, more than 60 years after the introduction of the Health Belief Model (HBM), Christoper J. Carpenter evaluated its effectiveness using meta-analysis which more advanced and powerful method for analyzing results because unlike Janz and Becker’s method, which they counted several statistical significant results in studies whilst Carpenter calculated mean effect sizes considering whole suitable samples as one sample. However, his review involved only 18 studies that assessed the model’s components (constructs) at two time periods – at the beginning and then sometime later. This is unique since the review included longitudinal studies only.

A summary of the Carpenter review:

His chosen studies covered mammogram screening, quitting smoking, drug-taking, dental care, condom use, cervical smear testing, and program attendance. As we can see, these studies have focused on our responses to screening services, medication compliance and repetitive behaviour such as condom use.

The following were his findings:

- Overall, perceived barriers were found to have the strongest correlation with the whole sample. (This is consistent with the previous two reviews).

- Perceived benefits had the second-strongest correlation with the whole sample.

- Perceived severity and perceived susceptibility had the weakest correlation with the whole sample.

- Perceived benefits were found to have the strongest correlation with preventive behaviours.

The updated Health Belief Model’s components;

The updated model consists of six constructs. It is as follows;

| construct | The belief of, |

| perceived susceptibility | the chance of affecting |

| perceived severity | the belief in the seriousness of the problem |

| perceived benefits | the effectiveness of the recommended action |

| perceived barriers | the perceived physical as well as psychological barriers |

| cues to action | triggers to take action |

| self-efficacy | the ability to take action |

What are the practical applications of those components?

Whenever we design promotional material or a program, we need to highlight HBM constructs in the following order in priority order.

- How to overcome barriers that the target population would perceive in engaging in the recommended behaviour

- How to highlight benefits in ways that the target population would perceive

- How to inform about susceptibility and severity in ways that the target audience would perceive

Using the Health Belief Model to Craft Health Messages

How does it occur according to the Model?

Our attitudes depend on six types of belief constructs:

- Perceived susceptibility to the condition

- Perceived seriousness of the condition

- Perceived benefits of the action recommended

- Perceived barriers to adopting the action recommended

- Perceived ability to perform the action

- Availability of cues to action to be taken

How does it help in message framing?

Let us think that we want to craft a message aimed at promoting a mammogram using this model.

1. To enhance perceived susceptibility – This is the strongest predictor of behaviour change. So, it is critically important to spend more space and time on this element than on other constructs.

How can we do that?

– The inclusion of a visual that resonates with the target audience

– Prompting them to think of someone of their age, gender and other characteristics with the condition

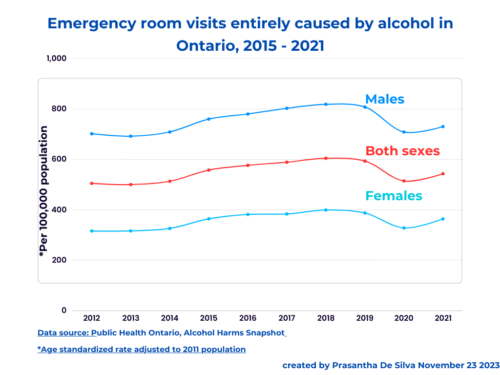

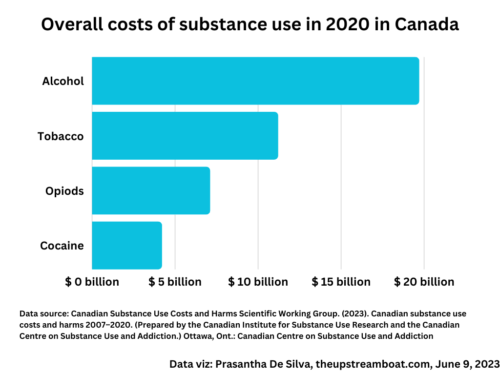

– highlighting risk factors and their strong relationship with the condition. We could use age and sex-related statistics!

– Showing how soon one could get the condition in the presence of those risk factors

– If possible, use a celebrity with the condition

If we are working with a team, we could brainstorm to come up with novel ideas.

2. To enhance perceived seriousness – This could be highlighted by using visuals, risk levels of death, disability, loss of income, family, and other relationships if the intended audience is affected by the condition.

3. To assist in perceiving benefits – highlight personal benefits specific to the target audience when compared to someone with the condition.

4. To overcome perceived barriers – addressing myths, increasing availability and accessibility to either products or services and citing places where they could obtain those.

4. Cues to action – frequent reminders, incentives, small gifts, highlighting participating rates, organising launching events, volunteer projects, T-shirts, mass walks, runs, enhancing the attractiveness of the message using white space, rhyming phrases, using the same message in different ways at different places.

6. To increase self-efficacy – providing training, simplifying the recommended action, opening more training places with attractive enrolment packages, positively reinforcing desired behaviours, and actions, and regular skills assessments.