Although behaviour change occurs in a continuum, researchers have identified stages of self-change in some behaviours such as quitting smoking. Let us embark on this journey starting 37 years ago:1983.

1983: “Stages of change”

Since the early 1980s, two researchers – James Prochaska and Carlos DiClemente – had been working with smokers who wanted to quit. They observed that some quit without any outside help.

In order to explore the observation further, they recruited 872 middle-aged volunteers who were smoking from Rhode Island and Texas through a newspaper advertisement. After classifying them into five groups, the study participants were followed for two years.

Prochaska and DiClemente published their findings in 1983.

In this study, they conceptualized quitting as a process (a journey) someone goes through in several stages – not as a one-time event. They considered the quitters would journey through four stages: from pre-contemplation to contemplation, action, and maintenance. Based on that premise, the participants were grouped into the following categories:

Pre-contemplators:

- This group were those who smoked but had no intention of quitting; “There is nothing that I need to change”

Contemplators:

- Contemplators: Those who smoked during the year before the study but seriously thinking about quitting; “I know that I have a problem that needs to be addressed”; “But, I am not ready yet”; “I have other priorities at the moment”.

Recent quitters:

- Recent quitters: those who quit smoking less than 6 months.

Long-term quitters:

- Long-term quitters: those who had not smoked more than 6 months

Relapsers:

- Relapsers: those who attempted during the year before the study but failed.

Their study was not limited to describing the stages only; they wanted to find out how these volunteers “processed their cognitive and emotional challenges” throughout the stages.

“Processes of change”

Based on their prior knowledge, the researchers defined ten processes of change. These consisted of five cognitive and affective constructs while the rest were behavioural. The following were those according to their published paper with a sample item for each variable.

Cognitive and affective processes

- Consciousness-raising (getting the facts): “I look for information related to smoking”.

- Social liberation (notice public support): “I notice public places have set aside places for non-smokers”.

- Self-reevaluation (creating a new self-image): “My dependence on smoking makes me disappointed in myself”.

- Environmental reevaluation (noticing your effect on others): “I stop thinking that my smoking is polluting the environment”.

- Dramatic relief (paying attention to feelings): “Warnings of health hazards move me emotionally”.

Behavioural processes

- Self-liberation (making a commitment): “I tell myself that I am able to quit if I want to”.

- Counter-conditioning (substituting): “I do something else instead of smoking when I want to relax”.

- Reinforcement management (rewarding): “I am rewarded by others when I do not smoke”.

- Stimulus control (managing the environment): “I remove things from my workplace that remind me of smoking”.

- Helping relationships (getting support): “I have someone who listens when I need to talk about my smoking”.

How they assessed the change processes

The researchers created a 40-item self-report questionnaire to measure the change processes; and, the respondents answered the questions on a 5-item Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 – repeatedly).

In addition, their smoking status was also assessed and the respondents’ saliva was tested to validate self-reporting of their smoking status. During the two years of follow-up, the researchers interviewed them every six months.

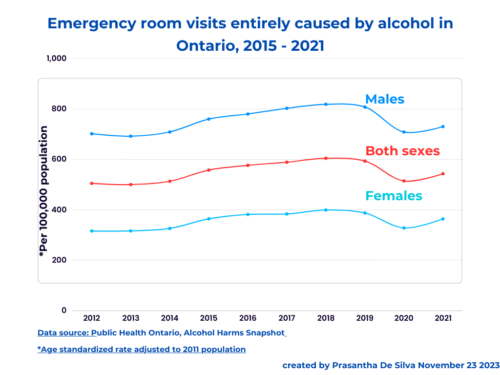

Their findings: Four stages of change

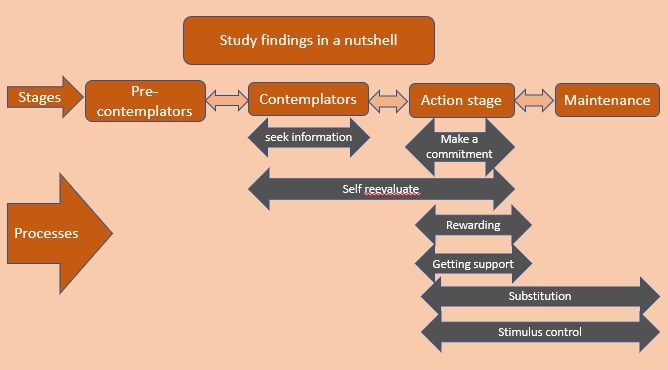

I depicted their findings in the following graphic; the integration of the four stages – pre-contemplation, contemplation, action, and maintenance – into the processes of change variables.

a

Let us go through the above graphic.

The pre-contemplators were not interested in seeking information in contrast to the contemplators. Making a commitment – for those in the action stage – seemed to be the most highly rated activity. The self-reevaluation became important for both groups who were in the contemplation and action stages. And, those in the action stage valued high being rewarded and getting outside help too. Finally, those in the maintenance stage rated high in coping skills such as substitution and stimulus control but, interestingly, not public support and being rewarded. Both maintenance stage strategies seemed to be useful in the action stage as well.

They also added more evidence to their previous percentage distributions of different stages in a population: 40% each in the pre-contemplation and contemplation stages, and less than 20% in the preparation stage. These proportions seem to vary by country; for example, 70% of Germany’s smokers were in the pre-contemplation stage.

1985

Self-efficacy, temptation, and stages of change

Our perceived ability to do a certain task will increase the chances of doing that task, according to Albert Bandura’s self-efficacy theory which was formulated in 1977. Research has shown this self-efficacy construct even predicts the likelihood of engaging in a certain behaviour/task including smoking. This association does not change with the type of measuring scale indicating how robust and powerful this construct is.

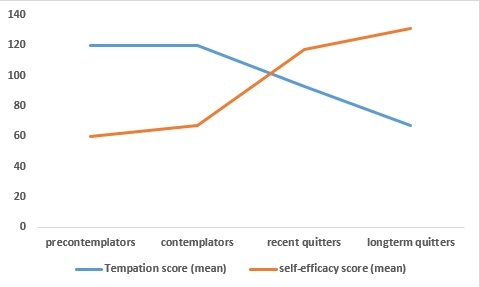

With regard to the stages of change, prior to 1985, Prochaska, DiClemente, and Michael interviewed 957 volunteers who were smoking with a self-efficacy scale. In addition to self-efficacy question items, it included questions related to the temptation level for smoking. The researchers hypothesized self-efficacy and temptation as a critical dimension – a mediator – in the behaviour change journey. They measured these constructs using a 31-item scale: self-efficacy by asking how confident they were to avoid smoking at home, office, etc, and temptation by asking how tempted they were to smoke in those situations.

This study found that the study participants travelled through different stages of change at different speeds and in different directions. For example, while some contemplators moved forward to the action stage, another group stepped backwards to the pre-contemplative stage – even some stalled at the same stage. I drew the following graph using the mean scores shown in their paper; we can appreciate how temptation and self-efficacy mean scores changed with the stage of change among smokers.

1992

Since the publication of the smokers’ two-year journey in 1983, a plethora of studies appeared in research journals on this subject. A decade later, in 1992, Prochaska and his research colleagues reviewed those and expanded their original four-stage model into a five-stage one; they added “preparation” as a separate stage in between the contemplation and action stages.

“Preparation” as a stage of change

The authors must have convinced that people tried (rehearsed?) some minor behavioural activities before they embarked on real action; for example, reducing the number of cigarettes, delaying the first one (DiClemente et al., 1991, etc.

In contrast to the preparation stage, those in the action stage stayed abstinent and maintained the new state for one to six months according to the authors.

Maintenance stage

Some of those who are in this stage may march forward to the maintenance stage abstaining from smoking beyond six months; they may adopt some more actions – such as counterconditioning and stimulus control – to prevent relapse. Research shows that those who enter this stage shuttle between this stage and other previous stages 3 – 4 times before stabilizing in the maintenance

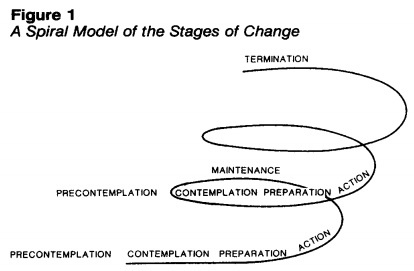

From a linear pattern to a spiral pattern

Before 1992, Prochaska and others considered that the shuttling through the stages follows a linear pattern; however, with the emergence of new evidence, they conceptualized the journey through the stages much like a spiral pattern – not linear.

Why spiral?

According to the new evidence, in the field of addiction, although we travel upward from pre-contemplation to maintenance through several intermediate stages, many may spiral down up to the pre-contemplation stage. Or else, they might stay at any stage sometime – sometimes even years. However, some of them may again move upwards armed with new attempts. Research has shown, according to the authors, that about 15% of smokers regressed to the pre-contemplation stage; however, 85% of them climbed again either to the contemplation or preparation stage.

1994: Weighing pros and cons: Decisional balance

In a paper published in 1994, Prochaska discussed another aspect of the stages of change model: the decisional balance or weighing pros and cons. He postulated that this construct was key to moving from one stage to another. He expanded Janis and Mann’s decision-making model which was introduced in 1977. The model argues that we make decisions after weighing four major consequences:

- Anticipated gains or losses to the self

- Anticipated gains or losses to the significant others

- Approval or disapproval from the significant others

- self-approval or disapproval

Prochaska reviewed twelve problem-behaviour that tested stages of the change model and the above four constructs; in fact, eight because each variable consisted of two opposing ends – gains or losses; and approval or disapproval. The study participants responded to the questions on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) not important to (5) extremely important.

Then came the most interesting part; those in the pre-contemplative stage scored higher standard T scores for the costs of changing behaviours than its benefits and the scores of those in the action stage reversed. In other words, pre-contemplators’ anticipated costs of changing behaviours were higher than their anticipated benefits of changing the behaviour; however, the pattern reversed among contemplators and those in the action stage; they weighed the anticipated benefits of behaviours rather than the costs of changing the behaviour. And, he reported another interesting finding; those in the action stage weighed lower the anticipated costs of changing the behaviour than the contemplators.

How can we translate this into action?

First, the above findings are strong because Prochaska drew his suggestions by analyzing studies addressing 12 different problem behaviours.

Although the above findings were from cross-sectional studies, we can theorize, as Prochaska did, that, first, we should raise the target audience’s perceived benefits of changing the behaviour to transport them from the pre-contemplation stage to the contemplation stage. Then, we need to reduce their perceived costs of changing to the new behaviour.

Interestingly, he further claimed that the rate of increase in the benefits was “at least twice as great as” a decrease in the costs when actors move along the stages from pre-contemplation to action.

Strong and weak principles

Based on the above results, Prochaska published another paper in 1994, confidently introducing two principles: the strong principle and the weak principle.

The strong principle

The strong principle states that progressing from the pre-contemplation stage to the action stage requires an increase of one standard deviation in the pros (benefits) of the healthier behaviour; the increase equates to a minimum of 20% increase of variance of the expected change. It also includes its own mirror images: increase in cons (costs) of not making a healthier change – either of failure to acquire healthy behaviour or failure to stop the unhealthy behaviour.

The 20% increase in the variance of either quitting benefits or costs of not changing the habit is not easy. How can we achieve that level? Prochaska opined that in addition to individual-level interventions, public health policies also need to be aligned. What are the individual-level interventions? They include raising the consciousness about the benefits of quitting and the costs of smoking and self-reevaluation skills. Assisting them to digest the benefits of quitting may be adequate, according to Prochaska. Obviously, we can raise its perceived benefits only.

Prochaska argues that public health interventions can be used to raise its actual benefits. how? It is by raising taxes; that smokers have to pay more to buy cigarettes. He suggests another interesting method that is still valid – raising their insurance premium and reducing insurance benefits!

However, no such interventions were available when he wrote this paper – in 1994.

The weak principle

Acquiring new behaviour carries some costs too. This weak principle addresses that problem; it says moving from the pre-contemplation to the action stage requires half a decrease of a standard deviation (0.5) in the costs of acquiring a new (healthy) behaviour. Unlike in the case of the strong principle, this equates to a 5% reduction in the variance of the costs considered. It also has its mirror image: the benefits of not making the behaviour change.

However, Prochaska observed that the weak principle was not as consistent as the strong principle across the problem behaviour.

2008

Fourteen years after the above study, researchers – Kara Hall and Joseph Rossi – tested these strong and weak principles for more problem behaviours. Quite remarkably, they found the same findings to the point of one standard deviation for the strong principle and 0.5 standard deviation for the weak principle. They meta-analyzed data from studies covering as many as 48 problem behaviours published between 1983 and 2003. The Preventive Medicine journal published the study in 2008.