Personal health narrative

“Alcohol is bad for your health”

We frequently find the above message in the media as a health education message; this is the dominant narrative.

In this narrative, we force readers to think about the illnesses that alcohol drinking may cause.

This frame results in two unintended consequences:

- Victim blaming: We can easily point the finger at the consumer when an alcohol-related problem occurs.

- We push ourselves into the industry’s playing field: Responsible drinking/ “nanny state” ideology.

Responsible drinking narrative

“Drink responsibly”

The industry invariably turns back and says that,

- “Alcohol-related problems are not their responsibility;

- And, it is the consumers’ responsibility; they should “drink responsibly”;

- Or else, “Need to target those behaving irresponsibly”.

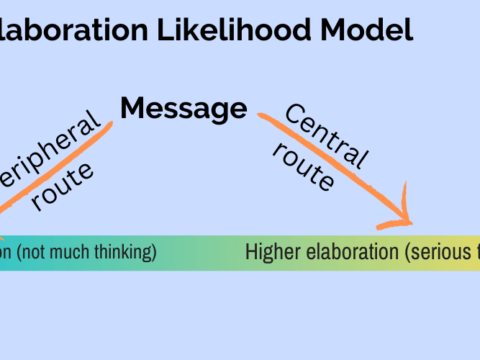

This individualistic, neoliberal thinking dominates even in the public health field when it comes to interventions; the most popular intervention is to educate people about the dangers of alcohol consumption and “responsible drinking”; of course, it has to be done. But, that alone is not public health.

We can find parallels of this individualistic thinking in the popular “Maslow’s pyramid” as well. Social psychologists explain this personal discount as a “Fundamental Attribution Error”; we are hard-wired to attribute responsibility to personal features rather than environmental settings.

Human rights narrative

“It is about personal freedom”.

It also arms them with another rhetoric: A human rights issue: “It is about personal freedom“.

All these claims are valid!

- We need to educate about the harms related to alcohol consumption.

- We need to identify problems drinkers,

- We need to provide health services for those who seek treatment for alcohol-induced medical problems.

But,

that is not enough.

What about social responsibility?

We need population-level approaches too.

The transnational alcohol industry opposes whole-population approaches. Instead, they favour measures targeting problem drinkers. as we discussed earlier.

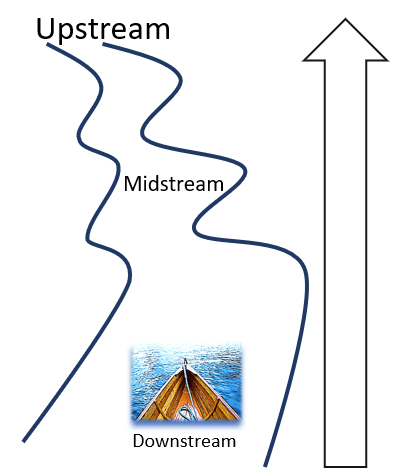

From portrait to landscape viewpoint

Let us shift from a portrait frame to a landscape frame

In contrast to the above-discussed “portrait” frame, the landscape frame “zooms out” and allows us to see the wider view.

With that, we enter into our playing field and invite the industry to play in our field.

I learnt this metaphor from The California Endowment training guide.

This frame-shifting is challenging because we are hard-wired with the Fundamental Attributional Bias.

However, it is possible.

For example, a few decades ago, tobacco control focused mainly on smokers. It has now changed to tobacco.

For example, the 2023 “No Tobacco Control Day” message was this;

Image link: Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)

How?

“Alcohol’s harm to others” (collateral damage) narrative

Highlighting alcohol’s negative impact on others is critically important; the industry prefers to emphasize alcohol misuse or abuse, problem drinkers, binge drinkers, and “alcoholics”.

The effect of one’s drinking is not limited to the loved one or significant other; it affects non-significant others as well much similar to the second-hand smoke.

Consider road traffic accidents.

Consider crimes.

Using the social justice narrative

We can zoom out further to cover a wider area by bringing social justice into the discussion. Social justice is the fundamental value of public health; it supersedes market justice.

The experts say that the market justice notion arises from Adam Smith’s idea that the “unfettered marketplace is the best way to serve the people’s desires”. This notion dominates to this day in the political sphere. As a result, governments resort to tax cuts for alcohol products and increase their availability and access instead of doing the opposite.

Using the social justice narrative for neighbourhood effects of alcohol

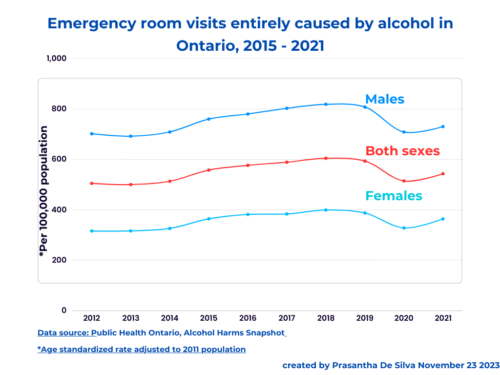

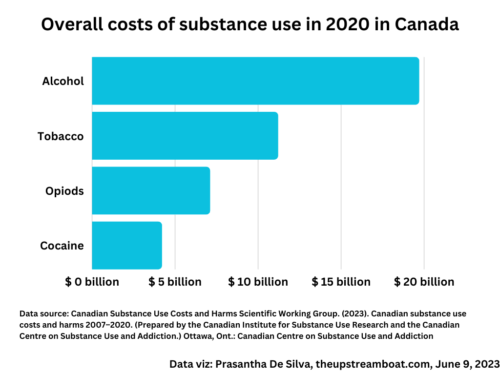

Access to alcohol is the greatest in lower SES neighbourhoods in Ontario. The alcohol-attributable emergency department visits increased by 17.8% over the two years from 2016-17 after the deregulation of alcohol sales in Ontario in 2015.

We know about the alcohol harm paradox – although those lower income drink less, they seek hospital treatment than those with higher SES.

Using the human rights narrative

We can also highlight human rights as the core value here referencing the 2005 WHO Framework for Alcohol Policy.

All people have the right to a family, community and working life protected from accidents, violence and other negative consequences of alcohol consumption

2005 WHO Framework for Alcohol Policy.

Using Rose’s prevention paradox narrative

If we do not have this data, we can use Rose’s prevention paradox. It is as follows;

“A large number of people at a small risk may give rise to more cases of disease than the small number who are at a high risk“.

Geoffrey Rose, Sick individuals and sick populations, International Journal of Epidemiology,

Volume 30, Issue 3, June 2001, Pages 427–432, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.3.427,

Norman Kreitman and Kari Poikilonein demonstrated this regarding alcohol-related problems; most alcohol-related problems arise from occasional consumers, not from daily and heavy drinkers. This is simply because the majority are “occasional” drinkers. The only way to reduce alcohol-related problems is to limit accessibility to alcohol in the community.